So, you want to know when Pisces is showing up? The whole point of this exercise wasn’t actually to look at fish in the sky. Honestly, it was because of some dumb bet I made with a guy called Greg, and I just had to prove him wrong. But hey, it led to a decent guide, so I figured I’d share the whole messy process.

I started this thing the way everyone does these days: typing something clumsy into a search bar. It got me nowhere fast. The results were all charts and tables and professional astronomy junk. I’m just trying to figure out if I need to stay up late on a Tuesday, not apply for a PhD.

The Initial Blunder: Phone Apps and Old Maps

My first move was downloading three different star-gazing apps. What a waste of time. They’ve got all these augmented reality views and zoom functions, but they’re too complex for a simple, direct answer. I was zooming in on Orion when I needed Pisces. That was almost two hours of pointless fiddling just figuring out what the buttons did.

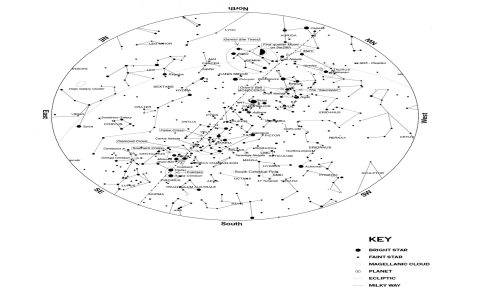

Then I pulled out an old book I had, one of those paper star maps you have to spin around. Talk about confusing. That thing was drawn for a latitude roughly near the Mediterranean, I think, and trying to adjust it in my head for North America just fried my brain. I threw the book at the wall. My initial “practice” was basically me being lazy and trusting complicated tools instead of just asking a simple question and logging the answer somewhere easy.

This whole mess started because I needed to save face.

See, I was on a camping trip with my wife’s extended family last fall. We were out by the fire, and Greg, my brother-in-law (the biggest know-it-all to ever breathe air), was babbling on about constellations. He pointed toward the sky and declared, all smug, “Look, there’s Pisces. It’s visible right now.” And he was wrong. But I didn’t have the proof right there, and I didn’t want to get into a stupid phone argument in the middle of nowhere. So I just nodded, let him have his moment, and secretly vowed to spend the next two weeks researching the constellations of the zodiac just to shove the facts into his face on the next family Zoom call.

I had to find the exact months, and the critical thing I realized those complex apps and books hide is the hemisphere difference. Greg probably got his ‘facts’ from some general website that assumes you live in a specific part of the world, which is why everyone gets this wrong. You need two separate lists, not one.

The Real Grind: Tracking Down the Facts

After ditching the apps and the dusty books, I switched to simply searching for specific, plain-language facts. I was literally typing things like, “When can I see Pisces if I live in Canada?” and then “How about if I was in Australia?” I collated all the basic info I could find, ignoring all the stuff about ‘right ascension’ and ‘declination.’ Just the months. That’s all I cared about.

The practice process became a data collection slog. I realized a constellation is ‘visible’ for a long time, but ‘best visible’ is what really matters. I ended up creating a super simple log of the best viewing times—when the sun isn’t messing things up and it’s highest in the sky.

And that’s the result of my two-week spite project:

The Simple Guide Log (Greg, Pay Attention)

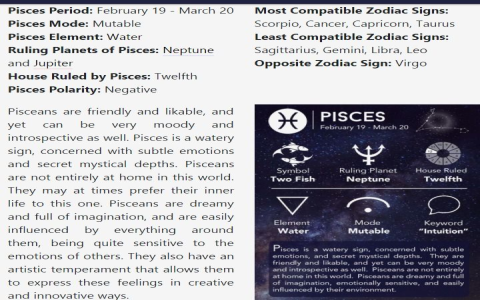

Northern Hemisphere (Think USA, Europe, most of Asia)

- The constellation starts showing up in the early evening around late July, but it’s low and annoying to find.

- Best viewing months: October and November. This is when it gets high enough in the sky right after sunset that you don’t break your neck looking for it.

- By late February and March, it’s pretty much gone, swallowed by the sun rising at the wrong time.

Southern Hemisphere (Think Australia, South Africa, South America)

- Down there, the whole sky feels flipped, which messes with everyone’s head.

- Best viewing months: September and October. It generally appears slightly earlier for them because of the way the Earth is tilted, but the principle is the same.

- It stays visible for a good chunk of time but gets harder to spot as you move into their summer months (December/January).

So, the conclusion is simple: If you’re trying to impress someone in the Northern Hemisphere, your best bet is to point at the sky in October or November. If it’s any other time, you’re probably looking at something else or it’s hidden behind the neighbor’s roof. And if anyone tells you they can see it clearly in February, they’re either lying or they’ve got their hemispheres completely mixed up.

I finally got to corner Greg on Thanksgiving. He still tried to argue. I just pointed him to my simple list. He shut up faster than a cheap laptop at a power outage. Worth the two weeks of messy research? Absolutely. Now I’ve got my basic star-spotting facts logged and ready for the next argument.