Unearthing the Old Project and Finding the Problem

Man, sometimes you just need to fix stuff the old-fashioned way, you know? I was having a nightmare this past weekend trying to get an ancient little home project working again—it’s this ridiculously complex controller I built back when I thought I was hot stuff. It manages the timers for the outdoor lighting and it decided, after sitting untouched for five years in a dusty box, to start blinking randomly. Absolutely maddening.

I dragged the whole setup out onto my workbench, which is usually just buried under takeout menus and old receipts, and started poking around. I found the original datasheet I printed out maybe fifteen years ago. It was yellowed and smelled like basement, but it was the key. All the configuration registers—the memory locations that tell the controller what to do—are listed in Hexadecimal. Of course, they are. Because back then, everyone used hex for memory addresses. It was the standard.

I finally tracked down the specific register that controls the main “blink cycle delay.” And what was the default value it was stuck on? Hex 63.

The Annoying Roadblock and Why I Went Manual

Now, I know what you’re thinking. “Just use the calculator on your phone, dummy.” Yeah, that’s what I tried first. But my laptop decided that moment was the perfect time to install a 45-minute mandatory security update. My phone battery was dead, charging in the other room. And I was already knee-deep in wires and solder smoke. I didn’t want to stop. I needed to know what ’63’ meant in binary right now so I could physically check the eight dip switches on this old board and see which ones were set wrong.

If I knew the binary code, I could figure out exactly which tiny physical switch I needed to flip to fix the damn timing problem. This wasn’t about being fast; it was about being stuck and needing to rely on my own brain instead of some piece of software.

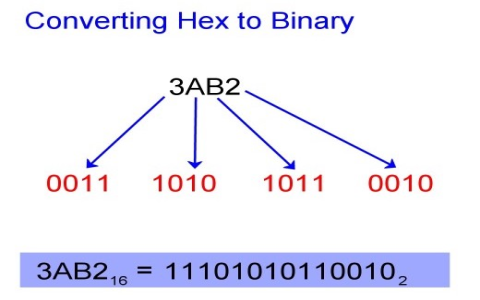

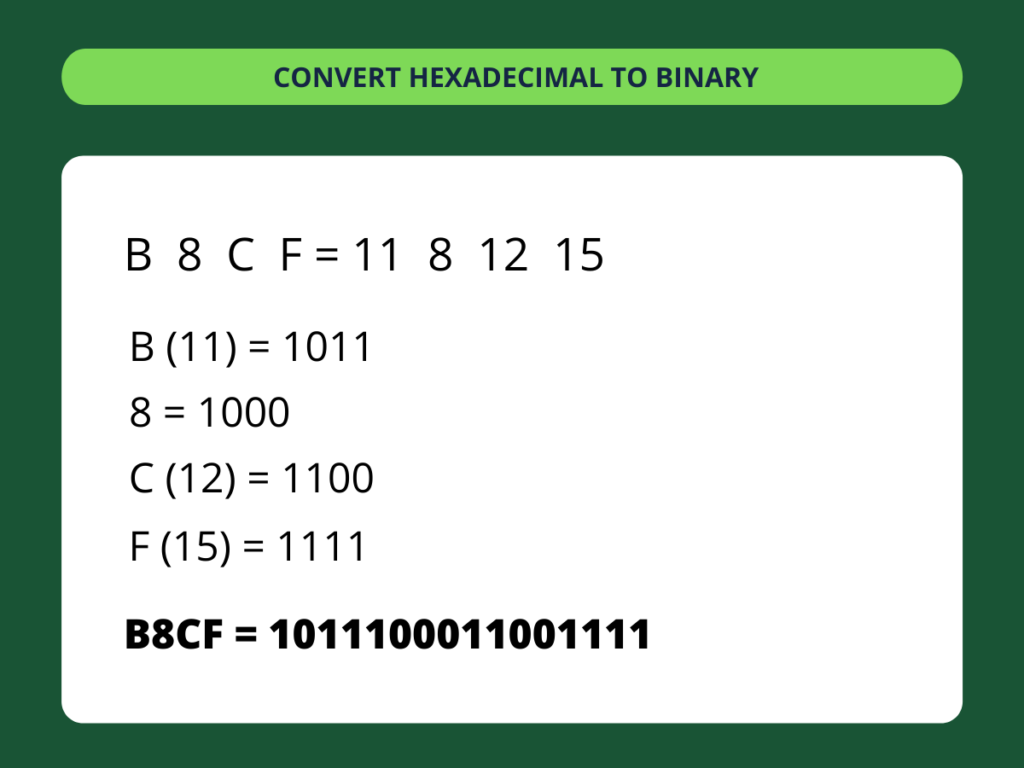

I grabbed a pencil—a stubby golf pencil, naturally—and a scrap of cardboard. I hadn’t manually converted Hex to Binary in years, probably since college, but I knew the trick. It’s actually ridiculously simple once you remember the pattern. You don’t convert the whole number at once; you convert each hex digit separately into its own group of four binary digits (a nibble). Four bits per hex digit. That’s the key.

Breaking Down Hex 63

So I wrote down 6 and 3, big and ugly, on the cardboard.

Step 1: Converting the ‘6’

You have to remember your 4-bit weights: 8, 4, 2, 1. To make a ‘6’ using those numbers, you need the 4 and the 2. The 8 and the 1 stay off (zero). I scribbled this down:

- 8 position: 0

- 4 position: 1

- 2 position: 1

- 1 position: 0

So, Hex ‘6’ is 0110 in binary. Easy enough.

Step 2: Converting the ‘3’

Next up was the ‘3’. Same weights: 8, 4, 2, 1. To make a ‘3’, you need the 2 and the 1. Everything else is off.

- 8 position: 0

- 4 position: 0

- 2 position: 1

- 1 position: 1

So, Hex ‘3’ is 0011 in binary. I was starting to feel like I actually knew what I was doing again. That felt good, honestly.

The Final Assembly and the Fix

The last step is the easiest: stick the two binary nibbles together in the right order. The ‘6’ came first, followed by the ‘3’.

Hex 63 converts directly to binary 0110 0011.

That eight-bit pattern (byte) was exactly what the controller was seeing. I immediately looked at the eight little dip switches on the circuit board that handled the cycle delay setting. They were supposed to represent that binary code, but they were set to something stupid, like 0110 0110. Who set that? Probably me, five years ago, late at night.

I grabbed a pair of tweezers and quickly flipped the switches to match the correct pattern: 0110 0011. The second I powered the board back up, the obnoxious random blinking stopped. The light cycle settled into the proper, boring delay. Done.

The whole thing only took maybe five minutes of actual work, but it was a great reminder. Sometimes, when you’re troubleshooting something physical or dealing with old hardware, you can’t wait for the fancy tools. You have to know the conversion method cold. It’s not complicated math, it’s just recognizing a pattern, and that pattern is often the fastest way to get yourself out of a tight spot. Next time my laptop forces an update on me, I’ll be ready with my golf pencil.