Man, let me tell you, when I first started digging into calculating the exact month and year pillars for a given moment in time, I thought it was going to be a simple lookup. You know, grab the Gregorian date, plug it into some old Chinese calendar chart, and boom, done. I was so wrong. Dead wrong.

My goal wasn’t just to find a chart; I wanted to build the engine myself. I was sick of using online calculators that were suspiciously vague or charged you subscription fees just to run a basic date conversion. I figured if I could code up a simple application to handle this core piece of metaphysics—the backbone of BaZi—I could trust the results implicitly.

The Year Stem: The Easy Part I Over-Engineered

I kicked off with the Year Stem and Branch. This part is relatively straightforward. It’s a 60-year cycle (the Sexagenary cycle). I grabbed the year, set up my baseline (I used 4 CE because it aligns nicely with the start of the Jia Zi cycle), and started throwing in modulo operations.

I wrote a couple of quick functions. One to map the year to the Stem index (0-9) and another for the Branch index (0-11). It was clean, mathematical, and predictable. I tested it against every year I could think of—1984, 1900, 2024. It worked perfectly. It gave me a false sense of security, making me think the rest of the project would be this easy.

The Month Pillar Trap: Ditching the Calendar

Then I hit the month. This is where everything went sideways. I initially tried to map the 12 Gregorian months to the 12 Terrestrial Branches (Yin, Mao, Chen, etc.). January is Month 1, February is Month 2, right? Nope. That approach is garbage.

I quickly realized that the Month Pillar isn’t based on the standard solar calendar we use every day; it’s based on the movement of the sun relative to the earth. It shifts according to the 24 Solar Terms (Jie Qi). Specifically, the start of the month, like the transition from the Rat month to the Ox month, doesn’t happen on the 1st; it happens precisely when the sun hits a specific degree of celestial longitude—the Jie point.

This forced me to scrap my simple date input system. I had to implement or reference an ephemeris calculation library just to pinpoint the exact UTC minute when each Solar Term started for any given year. I spent two weeks just wrestling with orbital mechanics data. I felt like I was writing code for NASA, not a simple pillar calculator. It was a massive drag on the project, turning a weekend hobby into a full-blown data science endeavor.

- I had to integrate a precise calculation for solar longitude.

- I created a massive data structure storing the approximate timing of the 24 terms for a hundred years to speed up searches.

- I wrote a specific checker function to confirm which side of the relevant Jie point the input date fell on, thereby locking in the correct Month Branch.

Finally, I had the Month Branch figured out. But that only solved half the problem.

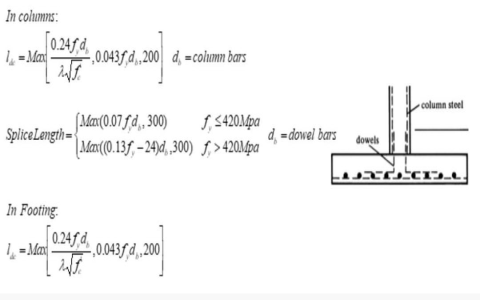

Breaking Down the Wu Hu Dun Formula

Once you know the Branch of the month (e.g., Yin/Tiger is always the first month), you need its Stem (Jia, Yi, Bing, etc.). And here’s the catch: the Month Stem is determined by the Year Stem. This is the famous Wu Hu Dun (Five Tigers Escape) rule.

When I first looked at the rules—if the Year Stem is Jia or Ji, the Tiger month starts with Bing; if the Year Stem is Yi or Geng, the Tiger month starts with Wu—I panicked. My immediate reaction was to build a monstrous series of nested `if/else` statements.

It looked something like this (in pseudocode):

if YearStem == Jia or Ji:

if MonthBranch == Yin: return Bing

if MonthBranch == Mao: return Ding

…and so on for 12 branches, repeated 10 times for all 10 Year Stems. It was a maintenance nightmare waiting to happen. It was clumsy, ugly, and hard to verify for errors.

So, I took a step back and looked for the underlying mathematical pattern. These cycles aren’t random; they’re elegant! I mapped the Stems 1-10 and the Branches 1-12.

I discovered the offset logic. The starting Stem for the Tiger month (Month 3 in the 12-branch system, counting from Zi) progresses in a fixed cycle of five. This meant I didn’t need 120 lines of lookup; I needed two lines of clean arithmetic using modulo 5.

The simplified formula I ended up implementing, which calculates the Month Stem index based on the Year Stem index ($Y_s$) and the Month Branch index ($M_b$), essentially uses a derived offset ($O$) and then applies the branch offset:

$O = ((Y_s times 2) + 2) pmod{10}$ (or using modulo 5 and adjustments for the pairings)

Month Stem Index = ($O + M_b) pmod{10}$

Once I implemented this mathematical shortcut, the whole section of my code dedicated to the Month Stem calculation shrunk from a massive 200-line block to a tight 15 lines. It was beautiful, reliable, and finally felt robust.

The Messy Reality of Implementation

So, did I succeed? Yes. I can input any date and time, and my code will reliably output the Year and Month Pillars based on the precise astronomical criteria and the Wu Hu Dun formula.

But here’s the reality check, the ugly truth they don’t tell you about building these tools:

My perfect calculation engine is running inside a hodgepodge of other necessary components. To handle the precision required for the Solar Terms, I had to use a specialized Python library. But for the front-end user experience and speed, I wanted a fast API, so I wrapped the whole process in a Go service. The database that holds my required time zone adjustments for historical dates? That’s a simple PostgreSQL instance.

Just like those big companies that use a dozen languages, my ‘simple calculator’ ended up being this complex system stitched together. I had to use Python for precision, Go for speed, and SQL for storage. The initial goal was simplicity, but the real-world complexity of precise time calculation—especially handling time zones, daylight savings shifts, and historical discrepancies—forced me to Frankenstein together the best tools for each task.

It works, though. Damn right it works. And now I know exactly why those commercial tools are such a pain to maintain—because the actual calculation is simple, but everything required to make that calculation work reliably for billions of different input times is a total technical mess.