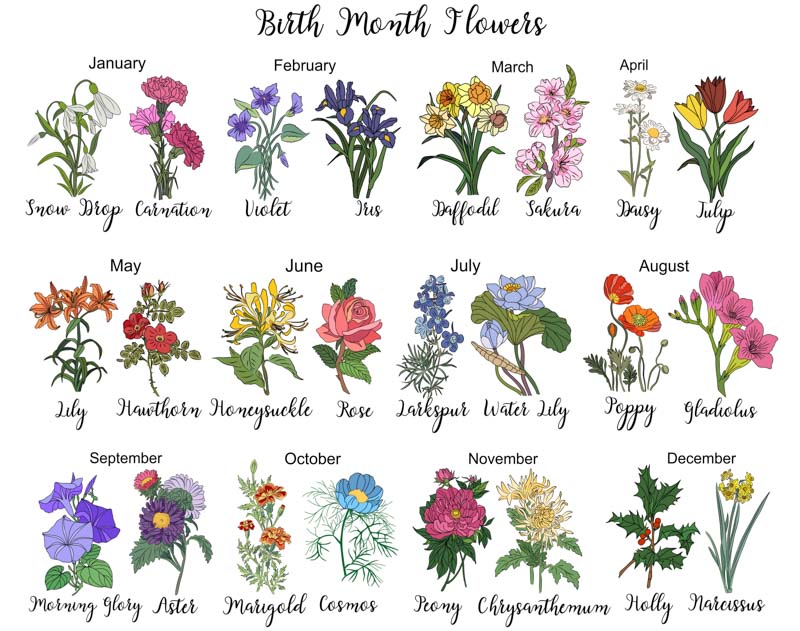

I swear, if one more influencer tells me my November birth flower is a Chrysanthemum because some shady online generator said so, I’m going to lose it. I spent three solid weeks tracking down the real deal, and let me tell you, the internet is lying to you.

The whole thing started because I needed to make a custom print for my nephew’s first birthday. He was born in early August. I figured, easy, I’ll just find his birth flower and get a cool illustration done. So I opened up maybe five different “free birth flower generators.”

What a total disaster.

One site yelled “Gladiolus!” Another insisted on “Poppy!” A third one, which looked suspiciously commercial, claimed it was the “Morning Glory.” I realized right then that these generators weren’t doing any historical or botanical verification; they were just copying whatever list they found first, or worse, pushing whatever flower was easiest to sell commercially during that month.

The Practice: Shutting Down the Screen and Hitting the Books

I got really frustrated. I hate being fed bad information, especially when it’s presented as fact. I had to figure out the truth. My initial plan—just Googling the official list—failed immediately. So I decided I had to track down the sources these lists should be pulling from: Victorian floriography guides, old gardening almanacs, and regional records. I threw my laptop aside. It was time for some real, physical digging.

Why did I commit to this weird, dusty project? Because I was completely trapped.

My building decided to replace all the ancient copper pipes, and for two weeks straight, the noise was unbearable. Drilling, hammering, shouting—it sounded like a war zone in my living room. I couldn’t concentrate on my regular work. I needed an escape. I started spending my entire day at the main city library downtown. They have this insane archives section, cold and quiet, full of books that haven’t been opened since Reagan was in office.

While everyone else was checking out bestsellers, I was requesting things like ‘A Dictionary of Victorian Flower Language’ (1884) and a massive volume called ‘North American Herbaceous Plants: Seasonal Bloom Cycles’ (1930). I started cross-referencing every single month, tracking when the flowers were actually native, when they were culturally significant, and when they were simply assigned a month by a random marketing group in the 1980s.

It was messy. I had stacks of sticky notes and ended up sketching out charts on graph paper just to keep track of the discrepancies between the U.K. lists, the common U.S. lists, and what the flowers actually did seasonally.

The Results: What I Dug Up and Why Your Generator Is Wrong

I quickly realized that most generators only stick to one commercialized list, completely ignoring the fact that many months have two, sometimes three, legitimate historical flowers depending on the tradition you follow. And some of those online results are just plain lazy attempts to fill a gap.

Here are just a few massive inaccuracies I pulled out of that library:

- January: Online generators love the Carnation. But historically, particularly in the UK traditions, it was often the Snowdrop. Carnations became popular later because they could be cultivated year-round and shipped easily.

- April: Almost every generator says Daisy. But if you look at older records, the Sweet Pea is just as, if not more, established in many regions, especially as a symbol of departure and well-wishes.

- July: This one is the worst. They always push Larkspur. But my archive books kept pointing to the Water Lily for true summertime beauty and innocence, especially in earlier American contexts. Larkspur showed up heavily after WWI.

- September: Aster is the safe bet, but the Morning Glory? That was a stretch. I found records pushing the Morning Glory mainly because the Aster was hard to distinguish from the October Marigold in early lists. Total confusion.

The generators are simply skipping the nuance. They pick one option, usually the commercial one, and blast it out. They don’t want you to know that sometimes, a month has three historically valid flowers. They just want the easiest answer to code into their little quiz.

I finally got the data I needed, proving that the August flower I needed for my nephew could legitimately be the Gladiolus, but only if I followed the specific North American list that favored height and strength. I ended up choosing the Poppy anyway, because historically, in many places, that symbolized peace and rest—something a new mom definitely needs.

So, next time one of those viral posts pops up, remember this: the people who built that generator probably spent five minutes on Google. I spent three weeks covered in library dust, surrounded by 100-year-old paper, just to find out they were all cheating.

Don’t trust the algorithm. Trust the archives.