Man, I was stuck. Really, really stuck last week. I had this big decision looming over my head about whether to ditch my stable, but utterly boring, main gig and jump into a wild side contract that promised a huge payday but felt like a massive risk. My brain was just cycling the same five arguments over and over again, driving me nuts. I needed something simple, something that could just kick me out of my own head, but I didn’t want to talk to another person about it. I just wanted a quick, personal reality check.

That’s when I remembered reading about the I Ching. Not the scholarly deep dive stuff, but the basic coin toss method—the I Ching 3. It promised a simple way to use an ancient system for real-world problems. I figured, what the hell? If it’s been around for thousands of years, maybe it’s worth ten minutes of my time. I decided right then and there to stop agonizing and start practicing. I wanted a record of exactly what happened, start to finish.

Setting Up the Practice and Formulating the Ask

The first thing I did was scramble around my office looking for three identical coins. I found three old, grimy quarters. Perfect. No need for fancy tools. Next, I grabbed a cheap little notebook and a pen. The instructions I’d skimmed said the most important part is the question. It had to be specific, immediate, and something you could actually act on.

I struggled here for about ten minutes. My initial question was, “Should I be happy?” Too vague. “Will I succeed with the new contract?” Too future-based and leading. I finally hammered it down to this:

- Should I formally accept the terms of the risky Project Y offer before the end of this month?

This forced me to focus. It gave me a clear timeline and a definite action—sign the paper or don’t. I wrote the question at the top of my page. I felt better already just having defined the damn problem.

The Casting and Recording Process

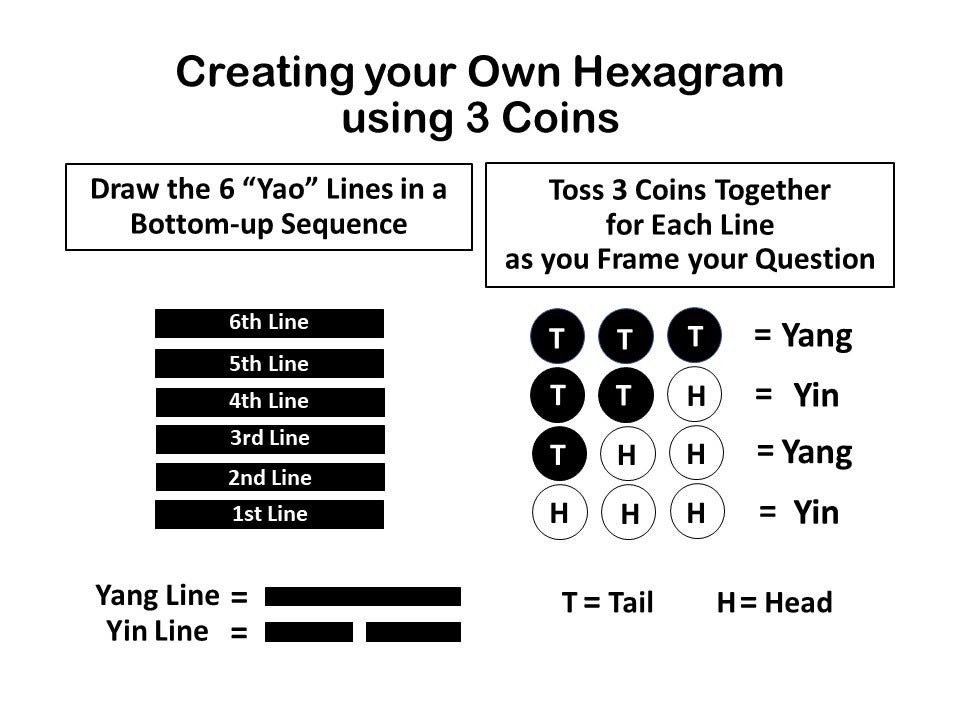

Next up, the physical work. I used the traditional system: Heads count as 3, Tails count as 2. We are summing the value of the three coins for each toss to generate one line of the hexagram. A score of 6 or 9 means a “moving line”—the key part that tells you how things are going to shift. A 7 or 8 means a stable line.

I focused hard on the question and started shaking those quarters in my cupped hands. I really took my time. I didn’t want to rush this part, I wanted to feel like I was committing to the process. I shook them, released them onto the desk, and carefully recorded the result. I did this six times, building the hexagram from the bottom up.

Here’s exactly what I got:

- Toss 1 (Bottom Line): 2+2+2 = 6 (Old Yin / Moving Line)

- Toss 2: 3+2+2 = 7 (Young Yang / Stable Line)

- Toss 3: 3+3+3 = 9 (Old Yang / Moving Line)

- Toss 4: 2+3+3 = 8 (Young Yin / Stable Line)

- Toss 5: 3+3+2 = 8 (Young Yin / Stable Line)

- Toss 6 (Top Line): 2+2+2 = 6 (Old Yin / Moving Line)

My final Primary Hexagram was formed by the results: Line 6 (top), Line 8, Line 8, Line 9, Line 7, Line 6 (bottom). I then drew the lines in my notebook: broken, broken, solid (moving), broken, solid, broken (moving). I immediately recognized that I had three moving lines. That felt like a lot of movement, and frankly, a bit stressful.

Interpreting the Chaos

I cracked open the cheap paperback I’d ordered on a whim a few months back. I didn’t use an app, I wanted the physical book in my hands. I looked up the structure.

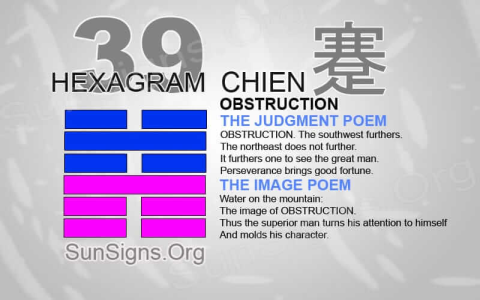

The Primary Hexagram I cast was Hexagram 39: Jian / Obstruction. The image is “Water over Mountain.”

Man, did that hit me. Obstruction. Difficulty. The text said something about “Movement stops before danger.” It immediately spoke to my feeling of being paralyzed about the decision. The general advice for Hexagram 39 is often: Hold back. Wait. Don’t press forward carelessly.

But the real juice is in the moving lines. Since I had three moving lines (6 at the bottom, 9 in the third place, and 6 at the top), I had to look at those specific statements. The I Ching told me that my situation was actively changing into something else. I had to calculate the new hexagram, the resulting or secondary hexagram, by flipping those moving lines.

6 (broken moving) becomes 7 (solid stable).

9 (solid moving) becomes 8 (broken stable).

6 (broken moving) becomes 7 (solid stable).

The resulting hexagram was Hexagram 58: Dui / Joy, Lake.

Wait, what? I go from total obstruction (39) to total joy (58)? That seemed contradictory and I almost tossed the whole notebook in the bin. But then I read the context. Obstruction isn’t permanent. Obstruction is necessary before you can find joy.

The Final Realization and Action

I sat with both hexagrams for about an hour. The I Ching wasn’t saying “NO, DON’T SIGN IT.” It was saying, “You are currently facing obstacles (39) that will require you to hold back, re-evaluate, and probably retreat from your current plan to achieve true joy (58).”

The Obstruction hexagram made me realize I hadn’t actually nailed down crucial logistical details in the contract—I was so blinded by the big paycheck I ignored all the red tape and potential headaches. I was heading into a huge mess. The movement to Joy wasn’t about the contract being inherently good; it was about the joy achieved by solving the current problem first.

My decision? I did not accept the terms immediately. I reached out to the client and negotiated three specific clauses that addressed the “Obstruction” I was worried about. I told them I needed clarity on scope and deliverables before committing. I took the advice: I stopped moving toward the danger and instead focused on clarifying the situation.

And guess what? The client agreed to the new terms, which totally de-risked the project for me. The I Ching didn’t predict the future, it just forced me to confront the present reality I was avoiding. It was a damn good practice run. I’m keeping those quarters handy.