Man, let me tell you about this whole hex 28 thing. For a while, it was just this annoying little pebble in my shoe, always cropping up when I was trying to get something done. You know how it is, you’re plugging away, trying to build something cool, and then BAM, you hit this weird snag that just doesn’t make sense. That was hex 28 for me. It wasn’t some grand, complicated error, just this persistent little pest that kept messing with my data streams, especially when I was dealing with some older systems.

I was working on a project that involved pulling data from this ancient sensor array. Seriously, I think it was older than me. The data came in raw, just a bunch of bytes, and my job was to parse it, clean it up, and make it look pretty for a dashboard. Easy, right? Famous last words. I started writing my script, felt pretty good about it. I’d set up my serial port, configured the baud rate, all that jazz. I was just expecting clean, numerical readings. But when I actually started receiving data, it was a mess. Bits and pieces were off. Numbers were looking weird. I’d print out the raw byte array, and there it was, plain as day, this sneaky 0x28 popping up in places it had no business being.

My Initial Head-Scratching Phase

My first thought was, “What the heck is this?” I just assumed it was some kind of garbage byte, maybe signal noise, or a bad connection. So, naturally, I tried to just strip it out. I wrote a quick filter: if byte equals 0x28, discard. Simple. Problem solved, right? Wrong. The data improved a bit, but it still wasn’t right. Some of the actual values I needed were getting mangled, or whole chunks of data were just disappearing. It was like trying to scoop water with a sieve. I felt like I was chasing ghosts.

I spent days on this, probably a whole week. I went through all my usual debug steps. I checked the wiring, I tried different serial port settings, I even swapped out the sensor module, thinking maybe it was faulty. Nothing. The 0x28 kept showing up, specifically at points where the data structure seemed to break. I was getting frustrated, pacing around the office, muttering to myself. My colleagues probably thought I was losing it. I re-read the ancient sensor documentation, which was barely legible, and still nothing explicitly mentioned anything about this specific hex code.

The Lightbulb Moment

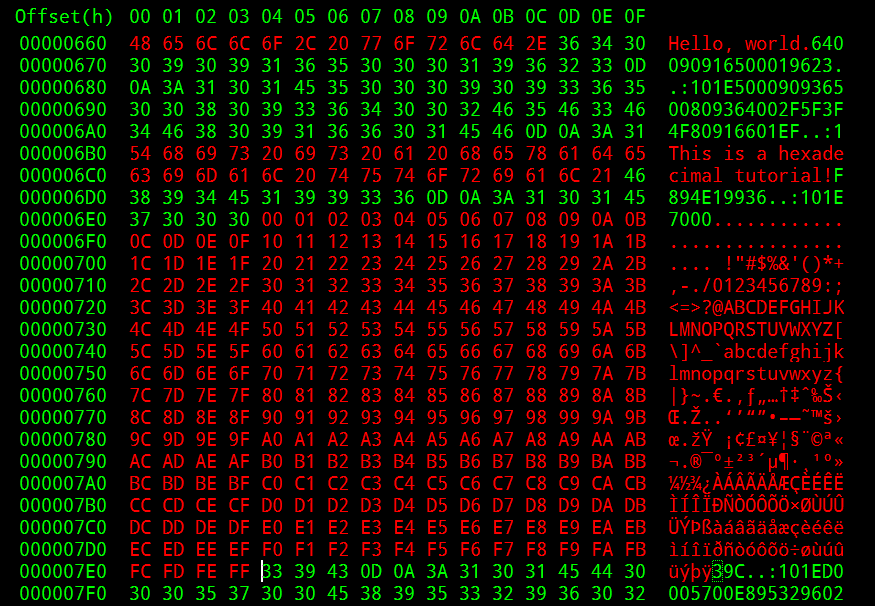

Then, one late night, staring at a hex dump on my screen, it finally hit me. I noticed a pattern. The 0x28 wasn’t random garbage. It was always followed by certain other bytes, and it always appeared before a specific sequence that seemed to mark the beginning of a data packet. It wasn’t noise; it was a delimiter. A very peculiar, non-standard, custom delimiter, but a delimiter nonetheless. It was acting like an opening parenthesis in a math problem.

I remembered reading something super obscure about this specific legacy system’s custom protocol. They used control characters for flow, not just for data. And 0x28, in ASCII, is the opening parenthesis. For them, in their weird little world, it meant “start of a structured data block.” I felt so dumb for not catching it sooner, but also incredibly relieved. It wasn’t an error; it was a feature, albeit a poorly documented one.

Putting It Into Practice

Once I figured that out, everything started to click. My approach completely changed. Instead of filtering it out, I needed to use it as a marker. Here’s what I ended up doing:

- Identifying the start: I modified my parser to actively look for

0x28. When it found it, it knew a new data block was about to begin. - Buffering the data: After detecting

0x28, I started buffering all subsequent bytes into a temporary array. - Finding the end: I had to figure out what marked the end of the data block. After some more digging, and trial and error, I found another unique byte sequence that consistently followed the main data. It was like their version of a closing parenthesis, but much more complex.

- Processing the block: Once both the start (

0x28) and end markers were found, I knew I had a complete, valid data block. Then I could safely go in and parse the actual sensor readings, knowing I wasn’t missing anything or mixing up data. - Error handling: I also added logic to handle cases where the end marker wasn’t found within a reasonable timeframe, to prevent my buffer from overflowing if a packet got corrupted.

It was a proper refactor of my initial simple script. I pulled out all the old filtering code and replaced it with a state machine approach. First state was “waiting for 0x28“. Once 0x28 arrived, it transitioned to “collecting data”. Then, upon seeing the end marker, it moved to “processing data” and finally back to “waiting” for the next block.

The Sweet Taste of Success

The difference was night and day. The data suddenly became clean, consistent, and reliable. All the readings were accurate, nothing was missing, and my dashboard started showing perfectly smooth graphs instead of jittery, broken lines. It felt incredibly satisfying, like I’d cracked an ancient code. My initial frustration melted away, replaced by that quiet pride you get when you actually solve a tricky problem.

It taught me a valuable lesson, too. Sometimes, what looks like an error or random garbage is actually a crucial piece of information, just presented in an unfamiliar way. You can’t always just sweep things under the rug. You gotta dig deep, question assumptions, and sometimes, you find gold where you expected trash. So yeah, that was my little journey with hex 28. A small byte, a big headache, and a even bigger lesson learned about not jumping to conclusions in coding.